Jenessa Williams talks character revelations, new audiences and social media pressures with the acclaimed author

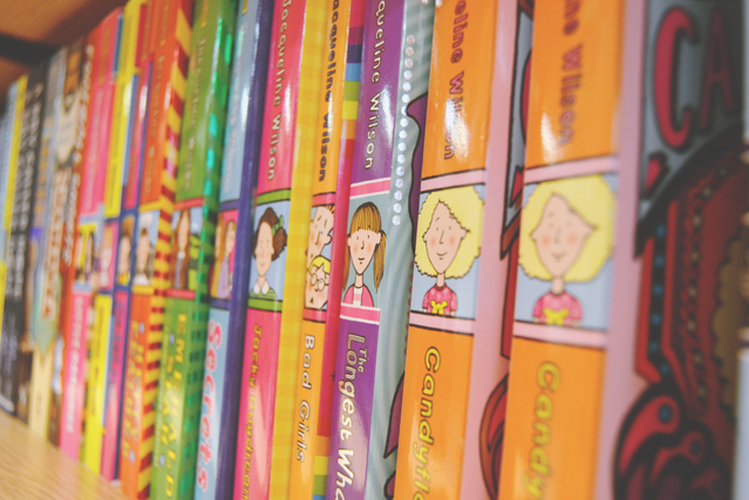

If you’re reading this in your twenties, chances are you owe a lot of your formative reading memories to Dame Jacqueline Wilson. Author of over 100 children’s books, her tales of less-than-ideal family circumstances provided catharsis for girls worldwide. Whether you saw yourself in shy April of Dustbin Baby, feisty Tracy Beaker or the growing pains of Ellie from Girls in Love, there was a friend for every occasion, a guiding voice that told you that is was okay not to be like everybody else.

Nearly twenty years after first discovering her books, meeting Wilson feels like a long time coming. When I arrive at her dressing room at the Carriageworks theatre (where she will later give a talk to hundreds of enraptured little girls), she is instantly recognisable – that short cropped white hair, cluster of chunky silver rings and patient, friendly voice that makes you feel as if she has all the time in the world for you. She's chatting with a girl named Faye - an adorable kid no older than eight with a bow atop her head that nods vigorously as Jacqueline promises to read the story that Faye has brought with her to gift to her idol, and permits her to name one of her characters in tribute. They've met four times now, and Wilson tells me later that she is one of her biggest fans. Nearly three generations after her first book, her affect on young girls is showing no signs of waning.

Tracy Beaker was the first book of mine that made a real impact

“I never really stop,” she explains, when I ask her how she has managed to maintain at least two book releases a year for well over three decades. “I’m about three or four chapters away from finishing the book I’m doing now and am already thinking hard about the next book, wondering about it so that by the time I finish this one I’ll be ready to start the new one. I’ve gotten used to working quite early in the morning – I like to go back to bed with my laptop and a cup of coffee and just get going. Sometimes, I’ll have a couple of days break, but that’s enough. I also find, weirdly, that if I’m not actually writing a little bit each day, I find myself having the most vivid dreams – it’s obviously that my imagination has gotten so used to working that it needs an outlet.”

Having covered difficult topics such as divorce, adoption and mental health issues in her novels, Wilson is lauded for not shying away from the tougher stages of childhood and adolescence. Despite a well-proven formula, she still feels nervous with every first draft (“You’d think that the more I had published and the longer I’d been doing it things would get easier, but it doesn’t”), and constantly wonders if the next book will be the one where people’s interest wanes. It’s clear that she’s particularly appreciative of the support her books have received and owes her enduring success to two characters in particular.

“There’s Tracy Beaker, the first book of mine that made a real impact. Of course, the long running television series (on CBBC) which helped enormously,” she smiles, "and then there was Hetty Feather, the first historical book which I wrote and loved doing. I wasn’t sure it was going to be popular at all, but now there’s been heaps of Hetty books since and the stage play and the television serial.”

What does she make of children growing up in today’s technological age?

“Hetty was the only book, as far as I’m aware, where it was actually somebody else’s suggestion. I was made a fellow of the foundling museum, and the director of that partnership actually said well, what we’d really like is for you to write a book about a foundling. I hadn’t really thought about writing a full on historical book, but as soon as she said that I started writing it almost immediately, and I loved doing it. I’m a bit of a technophobe, but it is so lovely to just Google a particular word to see if it was in use in Victorian times, and did girls wear socks or stockings or lace…to get the little nuances just right.”

Now immersed in drawing out the nuances from history, Wilson’s latest book, Wave Me Goodbye, follows Shirley, an evacuee during WW11 exiled to the countryside. After that will follow another Victorian novel, before a modern book, and then a trip right back to the 1920s. There’s talk of another TV series, more Hetty sequels, even her first feature film adaptation. With her schedule mapped out far ahead of her, Jacqueline remains rooted in what matters most to her – the innermost thoughts and feelings of children. What does she make of children growing up in today’s technological age?

I always intended Tracy to be mixed race, and nobody really picked up on it.

“I think the whole online bullying issue and the feeling like you’ve got to be a part of the gang and look like everybody else is really concerning,” she says. “Girls - not all girls, but some – can be so dependent on if they post something it has to get all the likes. It is such a pressure, and it would be lovely if somehow that could be toned down a bit for young girls.

And also, it’s wonderful that girls now have so many more opportunities and are expected to do well and have professions and total equality, which is of course fantastic, but they’re still expected to look really attractive at the same time. At least when I was in school you felt it didn’t really matter – you weren’t allowed to wear makeup or have a fancy hairdo, but nowadays there’s so many standards to keep up with – girls must have to get up so early! I just don’t get it, particularly the eyebrows – the really scary eyebrows! I’m not often on telly but if I am and they take me to the make up person, I always say please, no eyebrows!”

For the twenty minutes I spent in her company, I felt like the world may well have revolved around me

With our time drawing to a close, I thank her for making me feel included – with my own share of family issues growing up and a skin tone (not to mention the size of my hair) that made me feel like something of an outcast next to my school friends, something about Jacqueline Wilson’s characters felt like home. “Particularly Tracy Beaker?’ she asks. I smile back quizzically, unsure of what she means.

“Well of course, Tracy Beaker looks just like you,” she explains. “I always intended Tracy to be mixed race, and nobody really picked up on it. I just feel she looks mixed race – the way Nick has drawn her and the wonderful hair, it was always my intention.” With a revelation like that, my inner Faye surfaces, and I’m suddenly eight years old again, devouring books in my bedroom and finding kinship in these fictional girls. In a sea of underrepresentation, it feels like a personal gift to my childhood self, an acknowledgement of inclusivity.

We thank one another and take photos (“that was a truly star interview” she enthuses, politely), and I leave floating. Tracy Beaker was black, and even if this is a case of Hermione-esque hindsight, it’s a gesture of kindliness on Wilson’s part that could only comes from a lifetime of speaking to children and knowing exactly how to make them feel special. For the twenty minutes I spent in her company, I felt like the world may well have revolved around me. It’s hard to imagine that there will ever be a generation of young readers that she can’t make feel the same way.

Follow Jenessa Williams on Twitter @jnessr