Miz DeShannon speaks to the playwright telling the stories behind the partition of India, 70 years on

2017 marks seventy years since the Partition Of India, an event which saw the division of what had become known as British India and the creation of two brand new countries – Pakistan and Bangladesh. Countries created by dividing two of the most beautiful, fruitful and well-populated provinces of India, the Punjab and Bengal.

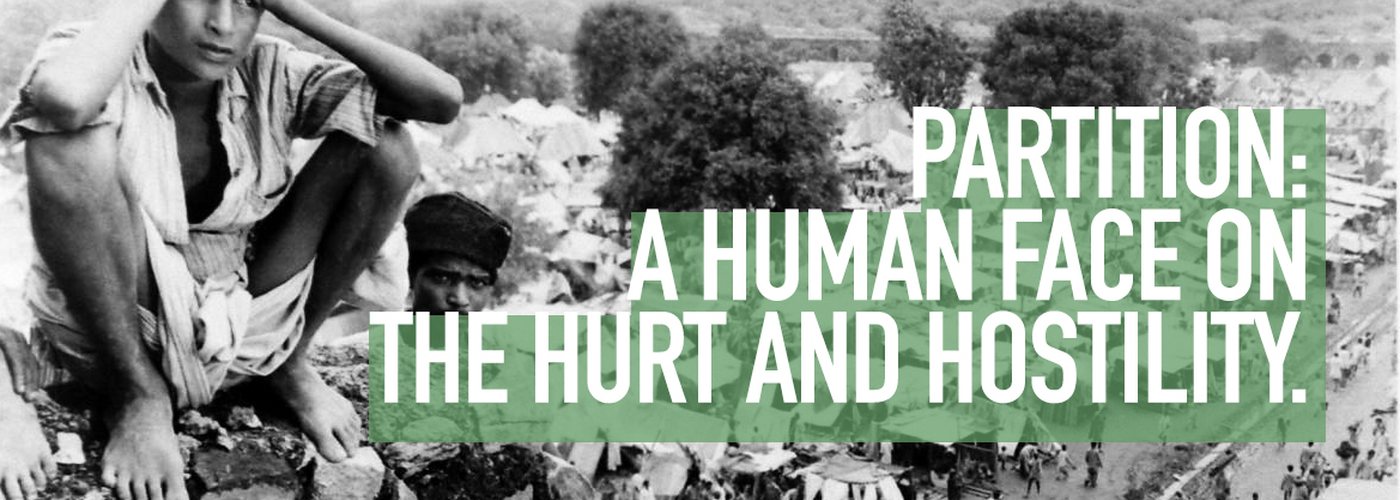

The partition saw the largest migration ever witnessed, displacing 12 million people, causing a mammoth refugee crisis, and untold acts of violence resulting in a loss of life reported at up to 2 million. Many of the truths about Partition - wholly disagreeable for the governments to discuss, and due to the abject distress and upset caused to the people who were there - have been covered up. Hand-me-down stories cling to the atrocities and the ills created between three religions that previously really had lived side-by-side in harmony for a long time.

The same date that is held as a celebratory day for India, Indian Independence Day, marks a sad moment in time for a lot of those who experienced the event. Packing decades of family belongings onto a cart, children being hustled at gunpoint, moving hundreds of miles across a new border to a new country through the night, and leaving friends and family behind, was not the happy revelation of finding a ‘Muslim Homeland’ it was publicised abroad to be.

A ‘human face’ is being put on the monumental event, an explanation of the hurt and hostility created and felt for generations to come

This is one of the most significant and untold stories of the last century, and through artists like Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy (who created HOME 1947 for Manchester International Festival) and Yorkshire playwright Nick Ahad, a ‘human face’ is being put on the monumental event, an explanation of the hurt and hostility created and felt for generations to come.

“Sanjeev Buttoo [BBC Radio Leeds’ Managing Editor] had an idea last year to mark the hundredth anniversary of the Somme,” says Nick, “and that went really well, so well in fact that for the first time ever the BBC funded a theatre tour, which went to schools in February this year. So we’ve worked together with me as a playwright rather than just a BBC presenter. We talked about some other historical events we could work on together, then it got really interesting, and our Partition idea became a much bigger thing than we expected.”

“I thought I’d just be writing a half hour radio play. It actually turned into a 45 minute piece because the BBC threw financial backing at it, we secured the BBC studios in Salford for recording - which are just about the best facilities you can imagine in the country - and then Sanjeev suggested that we should push it and put the play on stage. After discussing options I said as a throw-away comment it would be great to have it on at that [West Yorkshire] Playhouse, and all of a sudden there was a meeting lined up, the Playhouse came on board as co-producers as they loved the idea, and that’s where the idea of it being for both the radio and stage came from.

On the seventieth anniversary of Partition, what made you want to create a piece of drama around the event – purely personal reasons or other?

“There’s a character in the work who talks about stories, he says that all we really are is a collection of our stories, and I think that this is one of the most significant stories of the last century, which hasn’t really been talked about at all.

Midnight’s Children (Salman Rushdie’s 1981 novel) talks about it obviously, and there are lots of really factual books about Partition, but what you can do with drama is really get to the heart of something and what it is really about. Seventy years on I still see the effects of Partition today, and I still see it affecting relationships, so it just seemed a really obvious thing to do. And frankly, BBC Leeds wanted to do something about Partition, but they have a playwright who actually works in the building.” [he says with a smile, pointing to himself.]

So what sort of effects have you seen Partition having on communities and families?

“I’m mixed race Bangladeshi but Partition never loomed that largely in my life growing up because it wasn’t necessarily something that we talked about at home. I was at University when I first came across it as an issue. I had a group of Asian friends, at least 60% of whom were in what you’d call ‘forbidden relationships’, and I didn’t understand why. It was the first time that I’d never heard anything about this – Sikh in relationships with Hindu girls, Hindus in relationships with Muslims, and they all had to keep their relationships secret.

Then I started going out with a Hindu girl, we ended up living together, we were together for a long time, but she never ever told her family about me. Even though I’m mixed race, and ostensibly half a Muslim, it still would have been frowned upon, it wasn’t something that her family would have been happy with.

I think that kind of thing still happens today, I can see these things having happened in my own family, and I do think that religious divides are what lay at the heart of it, but realistically those religious divides weren’t that much of an issue until 70 years ago."

One of the most difficult things to understand is how people went from being neighbours to enemies. It’s like a nation lost their mind overnight

I know that the one time I spoke to my own father about Partition, he clearly remembered being separated from his friends, people who had been close neighbours for years…

Yes they literally shared food and helped each other out, they had different religions but that was it, and then it felt like – well this is explained in a brilliant book called Midnight’s Furies, and one of the most difficult things to understand is how people went from being neighbours to enemies overnight, and this book is called that because the closest thing they could find to what happened is the medieval furies. It’s almost like a nation lost their mind over night, it’s really weird what happened, but it did happen.

So how have you worked on the play, what did you do to make sure you found the right information?

I read LOADS, I watched documentaries, and being a presenter at BBC Radio Leeds I’ve got access to the BBC archives which is a fantastic resource, so I listened back to a lot of speeches, I re-read Nehru’s Tryst With Destiny, a lot of Jinnah, and I actually went back and listened to a lot of Churchill - who is not quite the hero that we are taught that he is – he has some interesting opinions about the Indian Sub-Continent.

I actually went back and listened to a lot of Churchill - who is not quite the hero that we are taught that he is

But I did all this research and then completely put it to one side, and examined exactly what the story should be, what the story is, and thought about how to take something so big and make it relevant to today. I had to sit on the shoulders of that research and then just write a story, so the story is about a Muslim girl and a Sikh guy, a young couple, who want to get married and their families are against it. Within that we have the Sikh boy’s Grandfather who actually remembers Partition, and the Muslim girl’s Mother who was told about it second hand.

I think what you have to with writing drama is look at all the information and think how it affects what happens today, because it isn’t a history lesson, it still has to be a piece of drama that has to entertain people. Don’t get me wrong the history is a fantastic lesson, but that’s not what this is, this is a piece of radio drama and theatre.

You’ve got two very different people leading the story there; one who actually experienced Partition and one who got information on it second hand – why have you made that distinction in the story?

I gathered some eye-witness reports that are incredibly powerful, and I really wanted to make sure those were represented in the piece, and I’ve taken a lot from some of those eye witness accounts. The other reason is that this piece is about learning from the lessons of the past, it exists so we don’t keep repeating the same mistakes from history, so the Mother who has heard about Partition second hand, her character encompasses how we can choose to pass on quite negative things to our children.

We see this with racism today, things like this are taught and learnt at home. In this case a hatred or suspicion of Sikhs and Indians, it’s something that has been passed down the family lines in the Muslim girl’s story, so my piece is about learning these lessons and understanding how if we’re not careful we can learn the wrong lessons from history. The two characters distinguish the very different sides to the stories of Partition, which were actually within event itself.

You grow up here and feel really English, but you’re reminded every now and then that you’re not

Some people have questioned why someone who is half Bangladeshi is writing this – it’s not because of my heritage, it’s because I’m a playwright, but all my work is about being second generation British Asian and particularly being mixed race, which means I have quite a keen sense of dislocation, displacement in effect, and not really knowing what ‘home’ is. I think that speaks to the subject of Partition just beautifully.

It was actually really sad when I went to Bangladesh to discover my roots, and if anything when I arrived there I felt an even keener sense of not having a place, because you grow up here and feel really English but you’re reminded every now and then that you’re not – growing up being subjected to bullying and name calling, and that’s not just someone saying a bad word to you, that’s a constant reminder that they think you don’t belong. But then I got to Bangladesh and realised that I didn’t belong there either. It’s very strange!

How hard was it for you to write this piece objectively then, and not fill it with experiences of your own and of your family’s?

TV writing is really structured, and there’s a reason for that – it works. I do tend to structure things quite rigorously before I actually write, as artists say about learning the rules and then playing within them, so I knew I was writing a play that was going to be on the radio and then on the stage so I created the structure and then put the emotional beats in afterwards, so you can be creative within the initial structure.

I know that with everything that I’ve written, I’ve put a bit of myself into, so I wrote a play called ‘My Mum The Racist’ which is about a white woman with mixed race kids, and she becomes racist – my Mum really was NOT happy about that, she wouldn’t come to see it! But there is honestly a piece of me in everything that I write, Partition was a slightly different was around as I was commissioned to write the play, but usually I write things on spec because I feel there’s something inside me that’s going to burst out and I have to say it!

And the result….?

Partition the radio play goes out on radio stations across Yorkshire at midnight on Monday, but then the same cast is on the stage at the West Yorkshire Playhouse at the beginning of September to do it on stage. They’re each going to be playing three different characters, with different voices and live sound effects on stage – the actors are basically presenting the radio play in person – it’ll be really cool.

It’s also the first time that BBC Radio Leeds and the Playhouse have worked together as well. It sounds trite, but this genuinely is a massive privilege, and I’m the first writer. It’s quite monumental in lots of ways and really relevant to the huge multicultural population in Leeds’ region.

Partition is scheduled to broadcast at 12am Tuesday 15 August on BBC Radio Leeds, and runs from Friday 8 September to Sunday 10 September at West Yorkshire Playhouse